(This is a wonderful story from Flux magazine on the lack of water resources in the Hawaiian Islands and their potential impact)

The view from Kailapa, the Hawaiian homesteads community on Hawai‘i Island’s leeward side, is remarkable not because of what you see but because of what you do not. No buildings on the makai side of the highway obstruct the panoramic view of the Alenuihaʻa Channel. Here, the water is a shade of blue so dark that you almost sense the 6,000-foot chasm between the churning ocean surface and the sea floor. Annie Kahikilani Akau, a native daughter of Kawaihae, named the subdivision Kailapa, meaning “lapping waters,” for the waves that hit the cliffs during high surf.

On land, what you do not see is a diversity of plant life. Instead, the two dominant species kiawe and buffelgrass, drought-tolerant vegetation introduced to Hawaiʻi in the 1820s and 1930s respectively, have replaced the area’s bountiful native dry forest. In 1913, botanist Joseph Rock was dazzled by the biodiversity of Hawaiʻi’s dry forest regions because it was “in these peculiar regions that the botanical collector will find more in one day collecting than in a week or two in a wet region.” On his tour of Hawaiʻi Island, Rock found himself upslope of where the Kailapa community is today, already beginning to note the extinction that was taking place. “Three miles south of Waimea, the land is known as Kawaihaeiuka, and must have been once upon a time covered in a plant growth similar to Puuwaawaa now,” he observed in his field writings. “In fact, the land is now very open and only a few trees can still be found, cattle having destroyed them very rapidly.”

In Kailapa there is not much soil left to see, either. When cattle chomp and stomp plants, saplings are unable to take root. Bare soil slips off the steep mountain slopes. Today, two thin layers of material above the bedrock of Kailapa consist of mostly pebble fragments and dead grass that has yet to blow away. A 2006 study of the area’s soils concluded that the severe nutrient losses “likely result from the strong downslope winds that can carry dead plant material, litter and/or ash into the adjacent ocean.” This fierce wind, called Mumuku, can also mean amputated, mutilated, or maimed.

Brandy Oye is familiar with this Mumuku wind. She was in high school when her father took her to visit the family’s lot in Kailapa in 1990. Under the blazing sun, he drove Brandy in their four-by-four pickup down a rutted dirt road past one of only two residences at the time, that of community stalwart Jojo Tanimoto.

“I remember passing Aunty Jojo’s house and I thought, ‘Where is Dad’s lot, and how do we know?’ Because there was no road. It was just offroading until Dad said, ‘Right here! This is it!’” Oye remembers. “And it was just red dirt and a flag pin.”

Teenaged Oye was dismayed. “I thought, ʻWhere are we?’ It was just red dirt and boulders.”

Oye was on the empty lot of what was to be her family’s home.

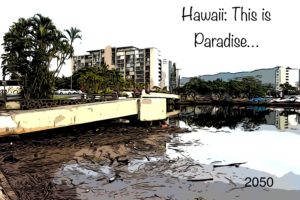

The 10,153-acre Department of Hawaiian Home Lands Kawaihae parcel, in which Kailapa sits, encompasses the entire ahupuaʻa of Kawaihae I. With an average annual rainfall of 120 inches in the forested mauka portion and around 5 inches at the coast just 7 miles away, this ahupuaʻa boasts one of the most magnificent rain gradients in the world. But you wouldn’t know it by the cost of water at the Kailapa homestead. Today, rates are over six times Hawai‘i county’s rates, and are slated to increase by 400 percent before the decade is out. The freshwater system that was meant to be a temporary solution has now been in place for more than 25 years. In addition to the exorbitant water bills, Kailapa residents face water insecurity.

To see the rest of the story